The acreage of vines planted in recent years is encouraging evidence of the huge optimism in the sector, but it’s creating a challenge which the industry is yet to fully address – where do we find the processing capacity?

According to WineGB chairman Simon Robinson, plantings of about 0.5 million vines in 2016, 1 million in 2017, 1.6 million in 2018 and 3 million in 2019, with the prospect of more in 2020, could result in a “serious shortage” of capacity.

“This potential shortfall has become more obvious over the past couple of years because of the high yields and it will become increasingly so as these new vines come to maturity,” he says.

Faced with this “pinch point”, some wineries will make use of existing spare capacity, others will expand, some bigger vineyards will build their own facilities and more contract-only businesses will launch, predicts Simon, who owns Hampshire-based Hattingley Valley. “It’s going to become more of a buyers’ market, though.”

For those looking to expand or build new facilities, securing planning permission shouldn’t be considered a fait accompli, with local objections always a potential problem, despite the broadly supportive national government position, he says.

“The extra plantings mean the industry will also face another challenge slightly further down the track which people aren’t yet talking about much – storage capacity. All these extra bottles will require space – and the right sort of space.

“The wine industry is innovative, but in the short term the biggest challenge could be felt by the growers who don’t want – or aren’t able – to have their own processing facilities,” says Simon.

Managing director of Bolney Wine Estate in Sussex, Sam Linter, believes the lack of nationwide capacity could particularly affect farmers diversifying into the sector in search of higher returns, who don’t have the desire or resources to launch a processing operation.

“If they want to sell grapes to brands already making wine, they need to have a clear plan for who they are going to sell to and what varieties those people will want, before they put any vines in the ground. The problem comes when people just assume that they’ll be able to sell the grapes.”

Sam’s confident the industry will evolve to address the shortage of winery capacity, but suggests it won’t be a quick fix.

“In the short term, there isn’t enough adaptability, or finance being lent into the industry,” she says. “We are evolving, but we’re still a very young and relatively small industry.”

Identifying this imminent need within the supply chain for additional capacity, Henry Sugden launched a new business in 2018. After 20-plus years in the Army and a spell in the City, he founded the Kent-based contract-only winery, Defined Wines Ltd.

“If you’re setting up a small- to medium-sized vineyard, unless you want to do everything by hand, it is not usually cost effective to invest in all the equipment you need, much of which will only be used for several days a year.

“Not only is it expensive to buy the equipment, it can be hard to raise the finance, you need the right team with the right skill set and getting planning permission – especially in National Parks or AONBs – can be difficult. We managed to get an EU Leader grant of about £170,000 but, by the end of this year, we’ll have invested over £1.5m to ensure we can provide state-of-the-art equipment for our clients.”

The Defined Wines approach is based on “giving choice and adding value” and they offer a full ‘crate-to-case service’ for still or sparkling wines or any part of this, whether that’s pressing, bottling, riddling and disgorging, labelling or temperature-controlled storage.

“We processed about 150t for 24 clients this year and, based on that experience, plan to expand next year,” explains Henry.

Understanding the planning system is vital for those looking to introduce or expand winery capacity, stresses viticulture consultant Matthew Berryman of CLM.

“It’s important to anticipate and mitigate all the restrictions and to have informal discussions with planners early in the process. There are some approaches that work and some that simply don’t. You ultimately need to come up with a proposal that shows you have considered all the factors and are prepared to work with the planners.

“It’s vital to cater for potential future expansion in a proposal,” adds Matthew. “Building in plenty of storage space, for example, means that you could use this at a later stage to expand your processing facilities if you decide to.

“You need to future proof yourself, but at the same time put together an application that doesn’t raise any red flags with the authorities.

“More buildings and facilities will definitely be put up – but there are currently sizeable Growth Programme grants available which can range from £20,000 to as much as £175,000 and viticulture projects can tick a lot of boxes in terms of the criteria to access these grants.”

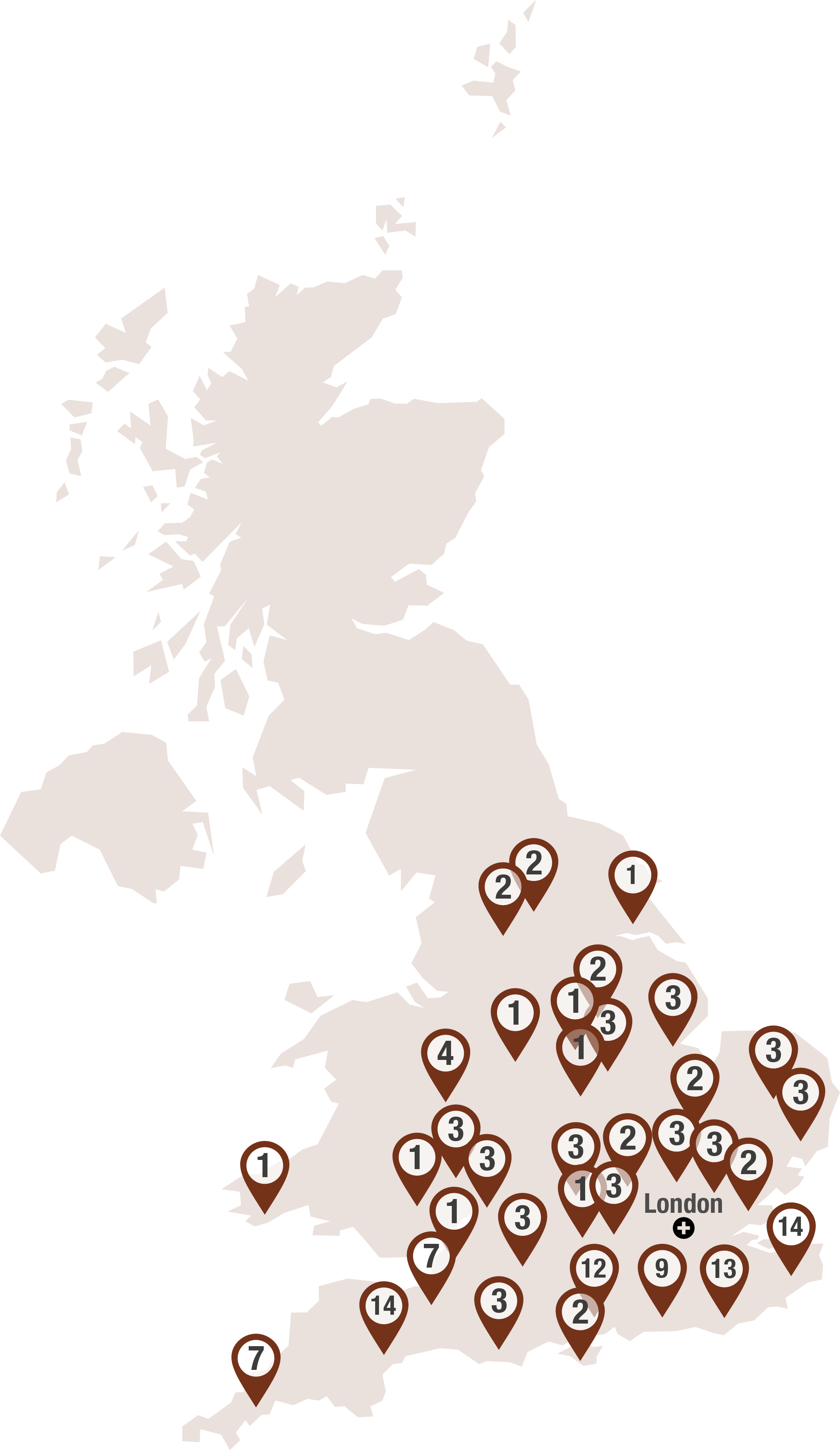

In 2018 the Wine Standards branch of the Food Standard Agency received wine production records from a total of 149 wineries. The map below shows the number of wineries in each county to give an overall idea of the distribution of winemaking facilities around the UK.