Advances in technology and wine science support winemakers in achieving the highest quality wines but blending still fundamentally relies on the capability of the winemaker, their palate and experience – and is a skill which must be learnt. Vineyard asks David Cowderoy, a winemaker of 30 years who has prepared blends for many wine styles all around the world, for some practical tips.

The blending process should start with establishing an objective, explained David. “This should be based on factors such as target style, release date, price point, and for sparkling dosage level, such as Brut, Extra Brut, Demi-Sec etc. But as you will need to repeatedly taste the wines, avoid planning to work on too many blends at once, as palate fatigue can be a major problem.

“One of the most important starting points for blending is to have a large range of wines with which to work. Creating a wine of complexity with just two or three wines is like trying to paint a picture with just a couple of colours. For sparkling wines, this is an area where Champagne producers excel.

“The winemaker has at their disposal numerous tools to achieve this, not just variety and clone but yeast strain, lees handling, oak treatment and so on. Plus, the 15% rule should always be kept in mind – 15% of a previous vintage or a different variety (or both) will not compromise the vintage on the label but may help the blend significantly.”

Getting the environment right

The ability to concentrate is one of the key requirements for tasting explains David. “Make sure the tasting room is quiet and free from any background aromas. The lab is not a good place due to chemical aromas and avoid kitchens as they can have lingering food smells. It’s important to allow plenty of time, avoid being rushed, avoid any disturbances – so turn off all phones.”

“Avoid taking samples for blending just after any SO2 additions as the aromas will be bleached out and dulled. But at the other extreme, young wines with little or no protection can rapidly oxidise, so I suggest filling the sample bottles with CO2 or dry ice before taking the samples.

“If the sample is highly charged with yeast it will not be representative and a good clarity is important. If the tank sample is cloudy filter it through a small capsule filter or at the very least take the sample from just below the top of the tank, where it will have settled more. But do not take directly from the top as this could have a degree of oxidation, especially if the tank is ullaged.

Equipment and analysis

“Blending requires plenty of identical tasting glasses, a spittoon, 100ml measuring cylinder, a 10ml pipette, sample bottles, a marker pen to write on the bottles and glasses – and I like to have my spreadsheet handy. If the aim is to achieve consistency across vintages, then samples from the previous vintage should be available for cross reference.

“An analysis is also useful, particularly for parameters where there are limits and implications, including free & total SO2, copper, TA, Alcohol, VA and residual sugar.

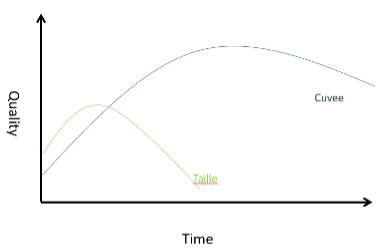

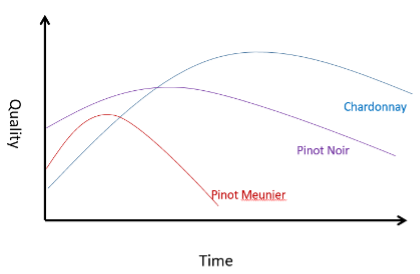

“Try and anticipate how the wine will develop – particularly important with sparkling wine where the ageing curve can vary considerably depending on variety and pressing fraction, as shown in charts 1 and 2.”

“There are many nuances that will influence the ageing curve but probably the most important is pH. The lower the pH, the longer the ageing curve, but not necessarily the greater the peak quality,” added David.

“Aromatic varieties can be particularly hard to blend unless you have prior knowledge of how they will age. Some can have wonderful floral aromas that work very well in a blend when the wine is young, yet totally dominate when the wine has some bottle age. Bacchus from very ripe grapes may be great when young but after time in bottle will become flabby and fat.”

“When tasting young wines, it is very easy to become distracted by characteristics of the wine that can be manipulated – in particular acidity. This of course can be reduced in the final blend and do not overlook the drop that will occur on cold stabilisation, which can be substantial. And of course, modification of acidity will also change the pH, with an effect on the ageing curve.

“Another distraction can be phenolics, apparent as astringency and/or bitterness. These can be reduced with proteinaceous fining agents but if there is a particularly problematic wine it is better to do this before blending rather than after. However, bear in mind how the wines will develop. Phenolics can sometimes give young white and rosé wines structure and texture but these do not tend to age well.

“Also, young wines can often be reduced which can be very off putting. The fruit also tends to be far less expressive when the wine is in a reduced state. This may dissipate with time and processing but for the purpose of blending it is better to treat the sample with copper to remove this.

“Young red wines high in dissolved CO2 can be particularly hard to taste as this re-enforces the acid and tannins. Try and remove the CO2 by shaking the sample, sparging with nitrogen or using a flash in an ultra-sonic cleaning bath.

“Conversely it is also very hard to extrapolate the effect of CO2 on a sparkling wine post-secondary fermentation. The best route here is to use a SodaStream to carbonate. The bubbles will be nothing like the finished product, but the effect on the trigeminal nerve will be the same.”

Top tips

David suggests keeping an open mind about what will work and what will not. “Sometimes the results can be surprising. An interesting example was a tank of Sauvignon Blanc from Bordeaux that had a problematic ferment and lacked varietal aroma. My initial approach was to use it in a second label but quite surprisingly it improved the overall quality of the first label, adding texture and mouth feel.”

Similarly, small changes to the blend can have a profound effect. “The most striking example I have encountered was a Chardonnay blend from the Languedoc, with which I was struggling due to a lack of aroma. Just 1% of Muscat lifted the nose and significantly improved it – but 2% was too much.

“In trying to produce a blend for a flagship wine, it is tempting to start with just the best wines, but this approach often doesn’t work. Just like two solo artists performing a duet – each will vie for centre stage and the overall result will not be as good as a lead singer with good backing.”

One of the most difficult scenarios for blending is where multiple products need to be blended from multiple tanks explains David. “The situation can rapidly become confusing with seemingly endless permutations. I have created blends from 1000s of litres to over half a million litres, and I find the easiest way to keep track and visualise is with a spreadsheet, see below a link to my spreadsheet.

“Once you have narrowed the blend to one or two possibilities, prepare a larger sample. This should then be evaluated later, in a more consumer like environment; at home or with colleagues. Even with sparkling wine blends the final blend should be something that pleases and is easy to drink.”

The winemaker’s palate is their key tool for blending, concludes David. “It is important to maintain and increase your tasting range to avoid ‘cellar palate’, which is a common problem, where winemakers try just their own wines. It is important to try a wide range of wines on a regular basis, including competitors. Trade tastings are particularly useful for this and acting as a judge for competitions can also be very useful for benchmarking your palate against other industry experts. The skill of blending is not an easy one or one that comes quickly but taken step by step expertise will develop to hone what is a very powerful production tool.”