Many wine producers are looking to making spirits particularly with the current fascination for gin, Ted Bruning an experienced observer of the drinks sector, puts the case.

In some respects, a vineyard is not unlike a smallholding. In particular, they tend to be somewhat cramped; to get by they have to squeeze as much as possible out of what acreage they have. But the nature of their operations means they have to tackle the job in different ways. For smallholders, it’s diversification: the goats pay the bills with their milk, meat, wool and hides; the little extras come from marginal crops such as poultry, top fruit, hedge fruit, garden produce, logs, kindling, and wild forage. Vineyard owners have few such opportunities because vines, to be blunt, are a monoculture. Maximisation can only come from intensification.

Nevertheless, skilled viticulturalists can play limitless chords and arpeggios across the keyboard, even more so since it was discovered that many parts of England proved ideal for sparklers. The méthode champenoise is the ideal elaboration of English wine, producing undeniably world-class wines as a bolt-on to existing businesses and thereby adding a hefty premium. But we’ve done that now: what next?

The answer ought to be to invest in a hand-beaten Portuguese copper pot-still, or a space-age German column-still, and press start. Let marc, eau-de-vie, brandy, palinka and hand sanitiser trickle into your spirit receiver and watch the money gush out. Sweet, eh?

But the industry has shied away from distilling, and few English wineries can boast a copper to polish. When brandy is a natural extension of winemaking and can command such a good price, why are winemakers so afraid of distilling?

It’s probably not the capital commitment. You can buy a 200l pot-still that will sit in a corner and take up no more than 6’ x 6’ for under £2,000, but there’ll be carriage and all sorts of extras, including a condenser and steam coil, that will push the price up to more than twice the cost of the still; then there are barrels at anything up to £250 for a 54-gallon hogshead. So even doing it on the cheap isn’t that cheap and does involve you in lots of preparatory work; tiling and pipework as well as assembling the whole shebang yourself.

The alternative is buying a still via a consultant who will have it shipped and installed for you, albeit at a price. You could spend a fortune, and many people do. But the point is that you don’t have to. The specialised nature, the availability, and the sheer quantity of the equipment you will need make a distillery start-up, even a modest one, more expensive than a brewery start-up but still much less expensive (and hopefully far more profitable) than buying a pub. So assuming your ambitions don’t extend to challenging Courvoisier, just how much capital should you reasonably expect to have to find? Or, since the sky is really the limit, a more sensible question might be: how little can you get away with? One consultant puts the bare minimum outlay at £100,000, but you can get away with far less because you already produce the wash and possess the bottling and labelling line.

Still, it’s not so much the investment that’s the drawback: your business plan should tell you what sort of return to expect. No, it’s the compliance.

HMRC, it is said by those who know, has rather relaxed its “ils ne passeront pas” attitude to start-ups in the 35 years since King Offa and Somerset Royal kicked off the whole craft distilling craze. It helps that you’re already familiar with the ways of HMRC. The forms you’ll have to fill in to complete your transition from winemaker to distiller are lengthy but, if you already understand the jargon, fairly straightforward. They are mainly concerned with security both of the product and of, the main thing, the duty and you will be required to raise a bond from a reputable lender. Even so, compliance is not a huge obstacle to the sprouting of boutique distilleries at wineries nationwide.

The grapes, though, are.

Take a trip to Cognac and you will see horizon-to-horizon rows of the Ugni Blanc vines that account for 90% of the plantings in the region. Their wine is very acid and as low in alcohol as cheap Liebfraumilch – say 7-9% abv. Ugni Blanc or Trebbiano Toscano doesn’t perform that badly everywhere: if it did it wouldn’t be so widely planted. But in the ungenerous soil of Cognac it does and that’s what the distillers want.

English winemakers don’t plant that kind of grape, nor do we grow enough to leave much surplus for distilling. In a bad year you can always rescue some revenue by distilling fruit that otherwise wouldn’t be worth vinifying. The spirit might not be brilliant – not good enough to sit for years in oak before being racked into Waterford crystal – but will make a perfectly adequate eau-de-vie for fruit liqueur, or could even fortify a sugary wine. Conversely a large part of a good harvest might be despatched to the still to make a first-class (and very expensive) snifter and to protect your prices by restricting the supply of your table wine.

Whether this justifies the faff of diversifying into distilling is another question: the dearth of brandy distilleries up and down the country suggests not. Not that English winemakers haven’t been tempted, but they have seen it as an occasional speciality rather than a regular offering. In the early days of craft distilling many a batch was sent off to be transubstantiated, but it was always an irregular affair. One such batch has just been bottled; in the mid-1990s, just before he retired, Kenneth McAlpine of Lamberhurst Vineyard tankered several thousand litres off to Julian Temperley’s Somerset Royal Cider Brandy distillery to be given the treatment. It has only now been bottled at 23 years old – but then, £125 a pop probably makes the wait worthwhile.

“Pricing”, said Bob Neilson of Brightwell Vineyard in lushest Oxfordshire, “is the key”. Brightwell has a limited quantity of Rush English brandy (named after a local historic landmark) privately distilled. Bob is very conscious that it is all cannibalised from his mainstream production, and it has to command a premium to be worthwhile and it should. The distilling process will concentrate the wine by a factor of 10, so every case of wine you could have sold for £60 wholesale will make you a bottle-and-a-bit of cask-strength brandy or three-ish bottles at 40%abv that you might sell for £90 wholesale. That’s without taking the distiller’s fee, maturation, packaging and duty into account.

Bob’s answer is the same as that given by every single artisanal food and drink maker in the world: quality. He stated: “To command the premium you have to take pains. The distilling is the easy part. Making the right cuts, controlling the temperatures, that’s the distiller’s skill. But the winemaker has to bring the best stuff for the distiller to work with because it’s a case of ‘garbage in, garbage out’. So no crap, please!”

Careful retailing helps maintain the margin: the brandy is on sale via Brightwell’s own shop and website, and the rest of its sale is in the local wine-merchants, grocers and farm shops that already stock Brightwell’s wines, and where familiarity has bred satisfaction. But the coppersmiths won’t be calling any time soon. “We’ve thought about it,” says Bob. “But it’s too much money.”

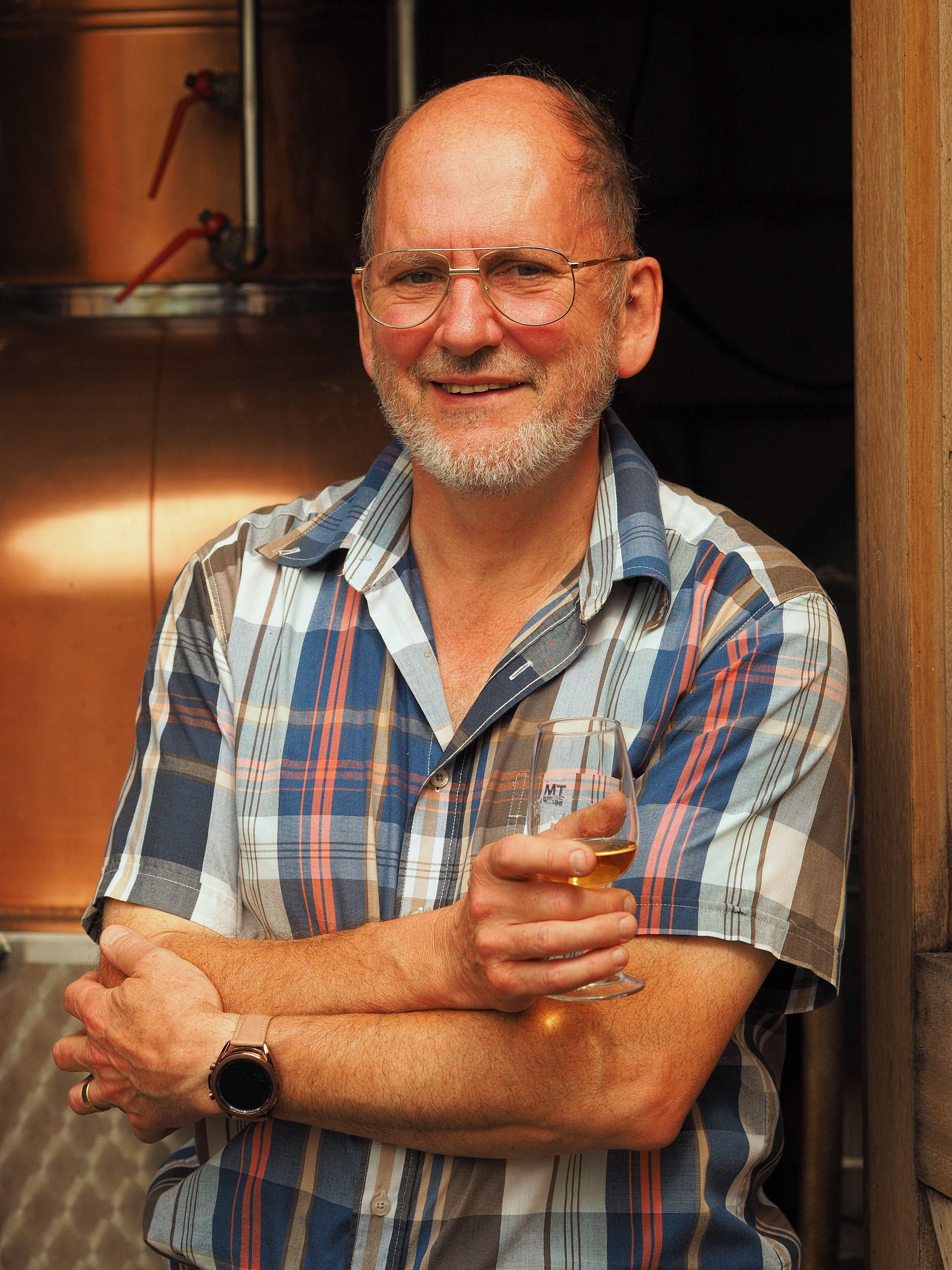

Mike Hardingham of Ludlow Vineyard in Shropshire jumped the other way in 2009 when he installed his German-made 200 litre still. He had been making both cider and wine since 2003, and as a Calvados lover he had always had distilling in the back of his mind. The decision to go ahead was triggered by a sample of brandy from Moor Lynch Vineyard in Dorset made by Julian Temperley. Mike realised that a distillery could earn its crust by working for as many masters as possible.

“Since then I’ve made far more for other people than I have for myself,” he said. “It sells very well and commands a good premium. Whether it’s a bad year and the fruit is short on sugar or a glut when you make more wine than you can sell, distillation can help make sure you don’t lose out.”

More and more distillers are taking his advice and looking for contract work. Yorkshire Heart, for instance, has its brandy made at Hooting Owl near York, and the legendary John Waters of English Spirit has moved out of his original home in Cambridgeshire to open not one but two facilities in Cornwall and Essex. Laurence Conisbee of Wharf Distillery in Northamptonshire started out as a cidermaker using apples scrumped (with permission) from the public parks of Milton Keynes. Now a distiller of cider brandy, grape brandy, whisky and just about anything else, Laurence will happily fill his still with whatever you bring him – even beer. He is also one of the first British distillers – if not the first – to dip his toe, metaphorically, into fortified wine and is perfecting a vermouth.

“There is so much opportunity that we’re buying a bigger still,” he said. “We’re targeting vineyards and especially breweries. Our next project will be a hopped beer – not too hoppy, though – with about a kilo of junipers dumped in it, then triple distilled for smoothness. We’re also making a marc which will be infused with herbs from local farms.

“Contract distilling is about 85% of our business now, but a distillery is a great bolt-on to a visitor centre and shop. It need not be all that expensive, so… why not?”

Ted Bruning