Mechanical harvesters for grapes were first developed in the USA during the 1950s, although a patent was granted for one early design as far back as the 1850s. The impetus for their development was the labour shortage on American farms thanks to the war effort. The women left behind had filled the gap as best they could, but another solution needed to be found to save time and labour.

The first cutter bar harvesters moved over the rows, hitting them with metal rods to shake or strip the grapes from their stems. The harvested grapes were dropped onto a conveyor which was then towed into a trailer to the winery. Later, air blowers were used to remove any remaining stems or organic matter that had been picked up in the process.

All of this shaking and squeezing could lead to the fruit being damaged, or even snap the vines, so the technology had to evolve – although damage to both grape and plant can still be a risk with machine harvesting today.

But before quality had a chance to become an issue, the technology hit a bump in the road in the United States. Unionised grape pickers blocked the commercial use of harvesting machines, so it was actually Australia where the first machine harvest market arose. This led to a rapid expansion of vineyards in the early 1970s, covering huge plots that would have been unthinkable without machines as the manpower to pick them would not have been available.

Modern machines usually rely on hydraulics to operate. They can be adjusted to work with different trellising styles and also be used on sloped terrain – up to a point – without causing damage to the vines. They still shake or strip the berries from their stems, but the rods that do this are now most likely to be rubber or fibreglass.

The decision to machine-harvest grapes is not one driven by quality. Practical concerns and financial factors are the cornerstones of choosing the method of harvest that works best in your own vineyard. Machines are estimated to be around five times faster than human workers in picking grapes – with a significant implication for the labour costs traditionally associated with harvest.

Advantages and disadvantages of machine harvesting

By removing the need for manual picking at harvest time, machines can remove many of the headaches associated with sourcing seasonal labour. Of course, the costs of each method have to be carefully weighed to ensure that contracting, hiring or buying the equipment is advantageous against the potential wage bill for grape pickers.

One of the reasons these costs can be made to stack up is the speed with which machines get the job done. Hiring equipment for one day may be more economical than paying workers to harvest over ten.

Machine harvesting also provides flexibility – they can be brought in at the drop of a hat to capitalise on fruit that is at its optimum ripeness, or to avoid a weather event that may damage the harvest. Assembling a workforce at short notice to pick by hand may not always be so easy, but equally when hiring equipment you are at the mercy of the contractor’s other commitments.

On the flip side of the coin, using a machine to harvest can limit winemaking choices. Many harvesters pick the individual grapes, leaving the stems behind. While this removes the need for a de-stemmer in the winery, it also takes away the option of whole bunch fermentation from the winemakers’ arsenal. Selective harvesting is also not an option where grapes are mechanically stripped from their vines. Naturally, these issues aren’t universal concerns, but they do bear consideration.

Contracting out machine harvesting

James Dodson, CEO of VineWorks, gave us the lowdown on contracting out a machine harvest.

What are the benefits of contracting?

“By contracting out to a machine harvesting contractor, you are saving on the investment costs and annual maintenance costs for a service that is required only once a year. However, it will be more profitable, due to the economy of scale, for a large producer with over 100 acres of vineyard to purchase their own machine. Labour can be challenging to source in the post-Brexit world, costly, and time consuming. A harvest machine can generally take up to 40 tonnes of fruit in an eight hour day, while it would take 80 labourers to hand pick the same amount and cost three times as much.”

What type of vineyards does machine harvesting work for?

“Harvest machines straddle the row, so normally a vertical shoot positioned (VSP) culture system is the most suitable. The trellis system is designed to concentrate the fruit zone in a vertical position allowing for the machine to capture the fruit efficiently when the vine is shaken. A system such as Geneva Double Curtain (GDC) would be unsuitable as the fruit is positioned high up, and spread out laterally, making it difficult for the machine to straddle the row.

“Trellis materials can be a concern. Metal systems are more robust than wood systems. If you are establishing a vineyard and are considering mechanising harvest in the future, then it is a good idea to prepare for it by using slightly higher gauge wires as the smaller gauges can break. A good quality wire, such as Bekaert Plus 2.7mm gauge for the fruiting and 2.2mm gauge for the foliage wires, is recommended. Other considerations are to have large enough headlands for efficient operation, an adequate area for unloading grapes, and relatively clean, disease free fruit. Otherwise, a select hand pick might be preferred.”

What preparations need to be made?

“First, and most critically, the vineyard manager will need to have done a comprehensive yield estimation per varietal. This is then communicated to the winery who may only be able to process 12 tons in one day. The machine harvester operator will then need to understand, for example, that only 12 tons can come off that day. With the sophistication of the machines today, they can track when the required tonnage has been achieved. Excellent communication between the vineyard manager, winery and the machine operator is critical to avoid over-harvesting and subjecting excess fruit to oxidation by having to press it the following day.

“There also needs to be a precise understanding of the logistics required to accept the fruit from the machine, and the transportation from the vineyard to the winery. This requires an adequate amount of dolavs (bins), pallets, a forklift to load the bins onto a trailer, and a tractor to transport them to the winery reception.

“It is also a good idea to tighten any foliage wires and anchor wires as the machine can easily collect these if loose. Access to water is also important for cleaning the machine after the harvest is done.”

Machine planting

Machines aren’t only useful for harvest. Harnessing their capabilities for planting vines is also an important labour and time saving practice, whether establishing a new vineyard or expanding an existing one. Machine planting can put 20,000 vines a day in the ground, probably 10 times what could be achieved by hand, depending on the soil type.

As well as reducing costs, machine planting is an important way of getting rows straight and spacing even, which makes the ongoing mechanical operations in the vineyard much easier. This precision also has an aesthetic benefit, having the vines lined up both vertically and diagonally makes for an excellent promotional shot!

The only limits for machine planting would be where there are very heavy clay soils or a very shallow topsoil with rock close to the surface that could limit the efficiency of the machinery and might make hand planting preferable.

In order to prepare for planting, the whole area needs significant cultivation.

“You need to subsoil, deep rip, and often leave a field to overwinter open, which is bad for soil structure and potentially for ongoing soil health,” explained Will Mower from VineWorks. “But it does get the field in a condition that can be machine planted. But when a vineyard has been planted, the vines will be in there for three decades, so you would never de-cultivate to the same extent as when you did the planting.”

The biggest issue associated with this is actually finding someone who has the equipment available for the deep cultivation required to create the requisite blank canvas. Will continued in more detail: “When you ask a contract farmer to prepare the ground for planting, they often don’t have the equipment required for deep cultivation because people just don’t farm like that anymore. They drill arable crops – either direct drilling or they have a very minimal soil disruption where they’re really working in the top few inches. Vineyards are being prepped down to twelve or fourteen inches, so people just don’t have the kit for it.”

Ultimately, a broadly cultivated field in advance of planting is a way of ensuring a successful outcome. On the day the whole ‘travelling roadshow’ of people, equipment and vines arrives and has a blank canvas to work with, allowing last minute changes to the configuration if circumstances require it.

Once planted, the young vines have the best chance of pushing out roots and finding an easy path to support the new canopy that develops above in well cultivated soil. The plants can find the nutrients they need, and moisture, without hitting a pan or a very solid clay surface that the roots just can’t penetrate. If only the rows were cultivated then there could also be issues stored up for the future with drainage and compaction.

Mandy and Simon Pryce at Vines of Cheshire made use of VineWorks services in the planting of their new vineyard. Having started planting their steepest slope by hand, which was so steep as not to be possible to plough with conventional farm equipment, they looked for a contractor to machine plant the flatter section. Perhaps surprisingly, some were not willing to travel as far north as the village of Backford, just outside Chester but VineWorks team were happy to make the journey.

“It took them about four hours to plant 2600 vines,” explained Simon. Both he and Mandy continue in full time employment alongside running their new business. “It would have taken us about four weeks to hand plant the same block during our evenings and weekends.”

Vines of Cheshire

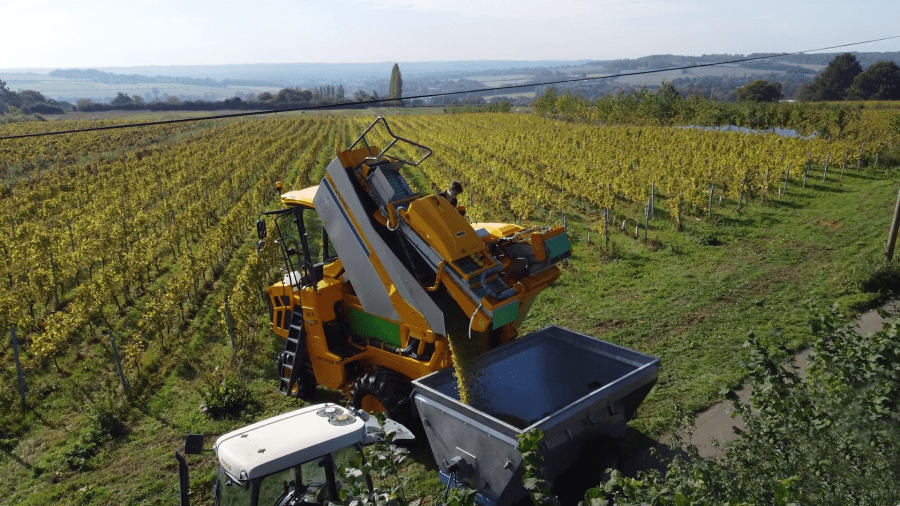

One of very few self-propelled machines available on the market

Braud developed their first self-propelled grape harvester in 1975 and in the decades that followed, New Holland Braud went on to become one of the leading names in the field. The New Holland Braud 9070l is perhaps the most suited to English and Welsh vineyards and is indeed one of the most popular such machines in the world.

Haynes Agricultural is an established dealership for these machines, based in Kent. Matt Pinnington is the Brand Manager for New Holland.

“It’s one of very few self-propelled machines available on the market,” Matt said. “It has a patented system of shakers, so it’s very gentle on the vine. It does a very good job of cleaning the crop quickly but it doesn’t bruise the grapes. It doesn’t damage the fruit at all.”

The 9070l can operate in most vineyards, including side slopes up to 30 degrees. It has a self-levelling system to automatically level the machine to match the vines alongside a hydraulic height system to match the height of the trellising. In fact, the main restriction on its use is likely to be getting it into the vineyard in the first place. Standing at four metres tall and nearly three metres wide, it may be overfacing for some points of ingress!

Despite its size, once put to work this machine is surprisingly agile. It has hydrostatic steering, so the front wheels can turn a full 90 degrees. As it can turn in its own width, it can manage on very small headlands, certainly compared to a trailed machine. The higher specification machines come equipped with GPS and a row tracking system, allowing it to steer itself along the row by virtue of onboard cameras. The benefit here is that the operator can focus on how well the fans are cleaning and how fast the conveyor is going – making sure that the fruit is at its best.

“But the main difference between the New Holland Braud 9070l and everything else is the Noria basket system,” Matt continued. “When the shakers shake the vines and the grapes fall towards the ground, most other machines use metal scales – a fish plate – to catch the grapes. But the grapes can bounce straight off and go onto the floor. And the fish plates open up around each vine, which creates gaps. The Noria basket system acts like a zipper and it is made of rubber baskets. So each rubber basket fits exactly around the vine which means you can’t lose any grapes onto the floor. After a few harvests, you can see witness marks on the trunks where the fish plates rub against the vine, whereas the rubber basket can’t do that, so there is no damage to the vines.”

The 9070l will set you back a cool quarter of a million pounds, plus VAT – a level of investment that is not going to suit every business. But it certainly has the technical specifications to warrant the price tag. It is no one-trick pony either, the harvesting head is removable, so a sprayer or trimmer can be mounted on instead. This means that the return on investment can be achieved more easily since the machine can be used all year round.

Easiest to use, with the gentlest grape handling

The Gregoire Harvester is one machine that makes significant savings on labour – in fact, it is the one that VineWorks have invested in for their own fleet. Dorian White, a technician at Kirkland UK, demonstrated the machine to customers at the end of the 2023 season. He is impressed with its capabilities.

“Twenty acres cleared and we harvested four different varieties of grapes in just under nine hours. And that wasn’t even at full throttle.

“Visibility for me was a key factor and also how clean the fruit was coming into the bins. This year we have had bountiful grapes but this machine hardly broke a sweat harvesting at 5.5kph.”

Croxford Wine Estates, a twenty four acre vineyard in Northamptonshire’s Nene Valley decided to go with the Gregoire GT3, having considered their options for a few years and visiting Gregoire at their factory.

“The driving force behind swapping to machine harvesting is cost, convenience and flexibility,” said Will Croxford, Director of Croxford Wine Estates. “After researching multiple manufacturers of grape harvesters I found the Gregoire GT3 to be the easiest to use with the gentlest grape handling. One of the features I most like is the ability to disengage the de-stemmer with a press of a button in the field. I also felt the handling of the grapes on the Gregoire GT3 is much gentler than other manufacturers, helping to keep berries whole.”

Will has built a relationship with Kirkland over the years, and they now run multiple machines in their fleet, finding their knowledge of the equipment to be excellent and also their stock of spare parts to be helpful in minimising downtime, when the need arises.

Gregoire at Redhill

For more like this, sign up for the FREE Vineyard newsletter here and receive all the latest viticulture news, reviews and insight