The origins of Pinot Noir

The Pinot family of grapes is one of the most ancient, being cultivated for almost 2000 years, with evidence of its existence in Burgundy predating Roman colonisation.

Due to this long history, a large number of clones have emerged, of which Pinot Noir is the most famous and widespread. Unlike its similarly famous and omnipresent peers, the relatively easy-going Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir is a mercurial vine – notoriously variable in its growth and difficult to tame in the winery too.

The tight clusters it produces are susceptible to a number of common hazards, making attention to canopy management of paramount importance when growing this fickle grape. Its thin skin, which can break easily and make the fruit open to attack from disease has earned it the dubious moniker of the ‘heartbreak grape’.

Despite the difficulties, Pinot Noir is one of the most commonly planted varieties in the UK. It is mainly used, predictably, for sparkling wine, although the volume being used for still wine is slowly increasing. Wine GB’s 2022-23 industry report revealed that the grape makes up 29% of total UK plantings, a close second behind Chardonnay at 31%. Pinot Noir précoce weighs in as the 8th most popular variety, but with that planting only totalling 66 ha, that equates to less than 2% of the total. The Champagne varieties claim 69% of the total UK acreage, so it is not a huge surprise that the quantities drop off sharply after the top three.

Character

Pinot Noir (also known as Spätburgunder)

- Pinot Noir buds early, which can make it susceptible to damage from frost early in the growing season

- The grapes are thin-skinned, meaning they can be prone to rot or mildew as well as viruses like fanleaf and leafroll

- Works well on calcareous soils and in relatively cool climates where it doesn’t rush to maturity preserving valuable aroma and acidity

- Difficult to vinify, needing monitoring and fine-tuning according to each vintage

- Produces wines with flavours that range from red berries like strawberries and raspberries to earthy notes of mushrooms and truffles. The wine has a captivating perfume, and its taste profile can evolve dramatically with ageing.

- The cool climate and range of diverse terroir in England and Wales is producing wines that often showcase a vibrant acidity and a remarkable balance of fruit and minerality.

Pinot Noir Précoce (also known as Frühburgunder)

- A mutation of Pinot Noir, Pinot Noir Précoce is a distinct and earlier ripening variety. It is well suited to the cool UK climate because of the potential for early harvesting.

- Its adaptability and reliable yields have seen it become increasingly popular with English and Welsh winemakers.

- Wines made with Pinot Noir Précoce are marked by bright red fruit flavours like cherries and redcurrants.

- In comparison with traditional Pinot Noir, the wines are often lighter and more approachable.

Pinot Noir clones

The infamous late 19th century phylloxera outbreak led to mass replanting – and it was also a catalyst for important European vine breeding and propagation programmes. Clonal selection is a slow and therefore expensive process for propagating desired traits in a vine. There are, for example, 48 Pinot Noir clones officially recognised in France. The certified clones are guaranteed to be virus-free and each carries an identifying number. One of the most popular in France is a first-generation Burgundy clone from the original 1971 release, number 115, which originated on the Cote d’Or. It is an early ripening vine, with only average susceptibility to grey mould despite that.

However, these are not the only options available to growers. Conservation collections planted in Alsace, Burgundy and Champagne between 1971 and 1995 include almost 800 clones in total. This large number allows vineyard managers to make their selection based on the most desirable characteristics for their situation, such as productivity, tannin structure or likelihood to ripen.

In Germany, clonal selection processes initially prioritised clones with looser bunches to avoid botrytis. Since the 1980s, aromatic intensity has come to the fore in selection alongside those traits relating to hardiness and productivity.

Pinot Noir and climate change

Thanks to its prestige, quality and proliferation, researchers are paying a lot of attention to how climate change may affect Pinot Noir across the globe. While it is difficult to frame climate change in a positive light on a global scale, it is likely to impact our perception of Pinot Noir and bring benefits, at least in the relatively short term, for English and Welsh producers.

One recent study looked at the influence that temperature had on the concentration of metabolites in the grapes. The research was carried out at Lincoln University on Pinot Noir vines grown at two different temperatures in controlled environment chambers by a team led by the Bragato Research Institute over two seasons.

They found that an increase in temperature led to a higher accumulation of most amino acids. This can have a positive impact on wine quality, producing wine with good complexity in terms of texture and mouthfeel. They are also the precursors for secondary compounds in grapes like thiols, esters and flavonols that play an important role in the flavour and aroma profile of the finished wine. This could lead to a gradual change in Pinot Noir’s characteristics, although more research is needed to map this shift in practice. Additionally, the vines in the study were irrigated and so the results do not account for water stress which may be as significant in its impact as an increase in temperature.

Looking closer to home, researchers used climate change models for the UK to simulate a projected repetition of the UK’s highest yielding season in 2018 cross referenced against the mean growing season temperatures in Pinot Noir producing areas of Champagne, Burgundy and Baden.

Their results suggested that “Large areas of the UK are projected to have > 50% of years within the bioclimatic ranges experienced during the 2018 growing season, indicating potential higher yields in the future.” Because of this, the researchers believe that there will be not only a greater potential for sparkling wines made from Pinot Noir, but also a “shifting suitability to still red wine production.”

They urge producers in the UK to sit up and take notice of these projects.

“The 2021–2040 time horizon is of particular interest to the expanding UK viticulture sector because decisions about what and where to plant now benefit from climate change projections to help avoid future potential lock-in.”

The science suggests that putting all your eggs in the sparkling wine basket in terms of both planting and marketing may not be the best strategy as the potential for changes in the UK’s suitability for growing Pinot Noir for still wines may be rapid.

Pinot Noir and SWD

There has been a lot of discussion about the rise of Spotted Wing Drosophilia (SWD) in the UK with the Royal Horticultural Society acknowledging that it is likely to become an increasing issue for cultivating vines in the future. Anecdotally, there appears to be some evidence that SWD prefers black grapes and that Pinot Noir may be especially favoured. Talking to vineyard managers around the country suggests that this cannot currently be confirmed as the picture is very mixed. What is clear is that more UK vineyards are experiencing SWD as the years progress and the issue is going to require significant industry attention.

Joel Jorgensen, Managing Director and Viticulturist at Vinescapes Ltd has been managing various vineyards across the UK for many years and has experienced the threat of SWD increasing since around 2016.

“We initially noticed it in Kent, near many top and soft fruit growers, particularly cherries and strawberries,” said Joel. “Since then we’ve seen the populations increasing rapidly and migrating gradually westwards across Sussex and more recently as far as Somerset, Devon and Cornwall.

“SWD certainly prefers red varieties, particularly thinner skinned Pinot Noir and Meunier and the earlier ripening Pinot Précoce. However, I have found larvae in Chardonnay and Bacchus too, but not beyond economic thresholds to justify treatment. The larvae feed on the juice and flesh as berries ripen and their presence often invites Sour rot, which can taint a batch of wine if not treated or removed at picking.

“Monitoring early via baited traps and regularly checking hedgerow fruits like blackberries has become routine for our viticulturists. We’re seeing some success in reducing populations with dead-end host plants and are incorporating these into more hedgerows at vineyards during the establishment phase. Reducing blackberry populations has significantly helped too.”

Looking around the UK, the picture is currently a mixed one. Polgoon Vineyard in Penzance and Bluebell Vineyard Estates in Sussex both report SWD damage to their Pinot Noir (and Rondo for Polgoon), with no sign on white varieties. Similarly, Brabourne Vineyard in Kent has seen SWD for the first time in 8 years on Pinot Noir, but not on the Chardonnay immediately next to it. Both varieties had the same levels of sugar and acidity, which suggests that colour was the make-or-break factor.

Thorrington Mill Vineyard has also had their first SWD issue in North Essex/South Suffolk, although they report a lower level visible on the Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc as well as the black grapes. They have a well-managed vineyard floor with a cultivated weed-free under row, so do not credit accounts that SWD may be coming in through weed cover. “This has probably been a perfect ‘bloom’ season for SWD,” a vineyard representative said. “I fear it is something we will need to be more on top of.”

Camel Valley in Cornwall has also seen SWD across their vines.

“We have seen it in Seyval as well as Pinot,” said Sam Lindo. “The first creature ever to want this variety. It looks like any potential negative effects have dissipated by the end of ferment and all is good right now. I think this year the SWD has come late enough not to be a problem.”

Finally, Astley Vineyard in Worcestershire appears to be the outlier, seeing evidence of SWD damage on their Bacchus but not the Pinot Noir. This certainly seems to be an area which will warrant careful scrutiny and further research in the future.

Picking suitable rootstocks

I spoke to Jon Fletcher at The Vine House UK to find out more about picking the right rootstock for your vineyard.

“Limestone based subsoils are ideal for vines in general, and the preferred soil type would be fertile and loose. Shallow dry soils can be difficult for Pinots and they do not do well with clay.

“Using a rootstock to match your soil type is very important. However, you should also be mindful of the characteristics of the vine graft you are going to grow on that rootstock.

“Suitable rootstocks for Pinot Noirs would be SO4, Binova in normal soils. If you have strong growing soil then choose a medium to weak rootstock such as 3309C or 5C. These will help the vine focus less on growth and more on crop.

“For close planting, less than 1.25 meters, also use a less vigorous rootstock such as 3309, 161-49 or 420A or Fercal in lime soil types.

“5BB Kober is best avoided as it’s very vigorous and not suitable for Pinot Noir.”

Making champion still wines from Pinot Noir

James Lambert is the Managing Director and winemaker at Lyme Bay Winery, Devon, producer of Lyme Bay Pinot Noir 2021, winner of silver medals at this year’s Decanter World Wine Awards and the International Wine Challenge.

“Since 2015 we’ve been looking to demonstrate what the potential for English still wines is and particularly Pinot Noir. We do that through a relentless search of pockets of land owned by growers who share the same passion as we do, looking for the highest degrees of potential ripeness and wines that can really showcase the terroir.

“The sales of English red wines are still only minuscule compared to the rest of the world but the climate is changing quickly, and the rate of change is impacting growing conditions in the UK. This is making them ideal for planting still varietals particularly Pinot Noir which is well suited to the cooler, longer growing season the UK provides.

“There is so much potential not just for Pinot Noir but other red varieties as well. With the right clones and the right grapes, in the right places, the UK is uniquely positioned to produce world class Pinot Noir – we just need a little patience!”

Making champion sparkling wines from Pinot Noir

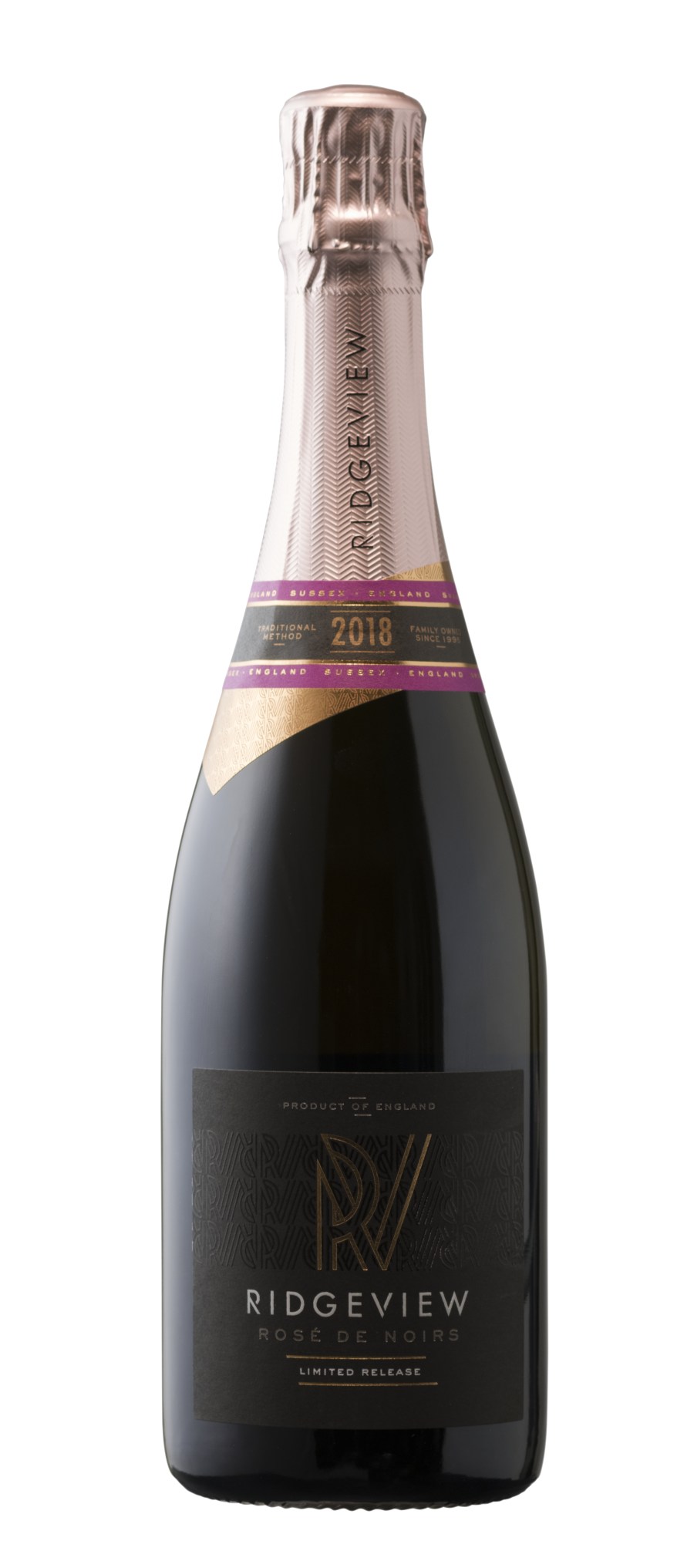

Simon Roberts, Head Winemaker at Ridgeview Wine Estate, Sussex, producer of Rosé de Noirs Brut 2018, the only UK platinum award winner at this year’s Decanter World Wine Awards.

“We have been working with the viticulture legend Marco Simminit for a few years now, he has been helping us redevelop these vines with a more synergized and regenerative form of pruning, and we really saw the “fruits of our labour “ (excuse the pun.) We had the best looking crop from our Pinot Noir and Meunier I have seen for a long time. The juice was equally impressive.

“Tasting it straight from the press we knew this would be the basis of either the Blanc de Noirs or the Rosé de Noirs. Quite delicate, but full of promise and complexity. For the Ridgeview Rosé de Noirs we only use the best fruit and if we don’t feel the fruit is good enough we will not make the wine. We look for rich fruits of the forest, cherries and spice, maybe some liquorice.

“The Rose de Noirs is one of our wines where the winemaker really has an impact. We use our interpretation of the Siangee method. We load the press at the end of the late shift and the fruit will stay in the press until the next day. The winemakers check the colour of the juice until we are happy with the extraction. We then press the fruit as a sparkling programme so as not to press out any bitterness or unwanted phenolics.

“Making the Rose de Noirs takes time, care and understanding of the fruit. This wine is always the most fun to make. One of my favourites. An example of the dedication to perfection that we hope to achieve in our winemaking for Ridgeview.”

Ditchling Common, September 27th 2023: Ridgeview Wine Estate