The wet weather, rationed armoury – and limited opportunity to use it – have created the perfect storm for downy mildew. Vineyard speaks to some of the experts for their tips on tackling this fungus-like disease with its potential to cause significant crop losses.

Downy mildew has been a frequently muttered word amongst vineyard managers this year – and the general consensus is that early detection and timely treatment is critical as a few infected leaves can result in a rapid spread of downy throughout the canopy with risks to the crop.

What is downy mildew?

“The weather has been perfect for downy, regular heavy rain causing splashing, and there is very little we can use against it on an organic vineyard,” commented Will Davenport, of Davenport Vineyards, Sussex. “The soils are wet, there is lots of moisture and most mornings a heavy dew can be seen as temperatures rise – steam can be seen coming of the land – all perfect conditions for downy mildew,” added John Buchan, agronomist. “There are many benefits of cover crops, but they do retain moisture and can provide an environment for perfect infection conditions for downy mildew. The weather has also been a challenge for product application – as we need to have enough hours without rain for them to be effective,” said John.

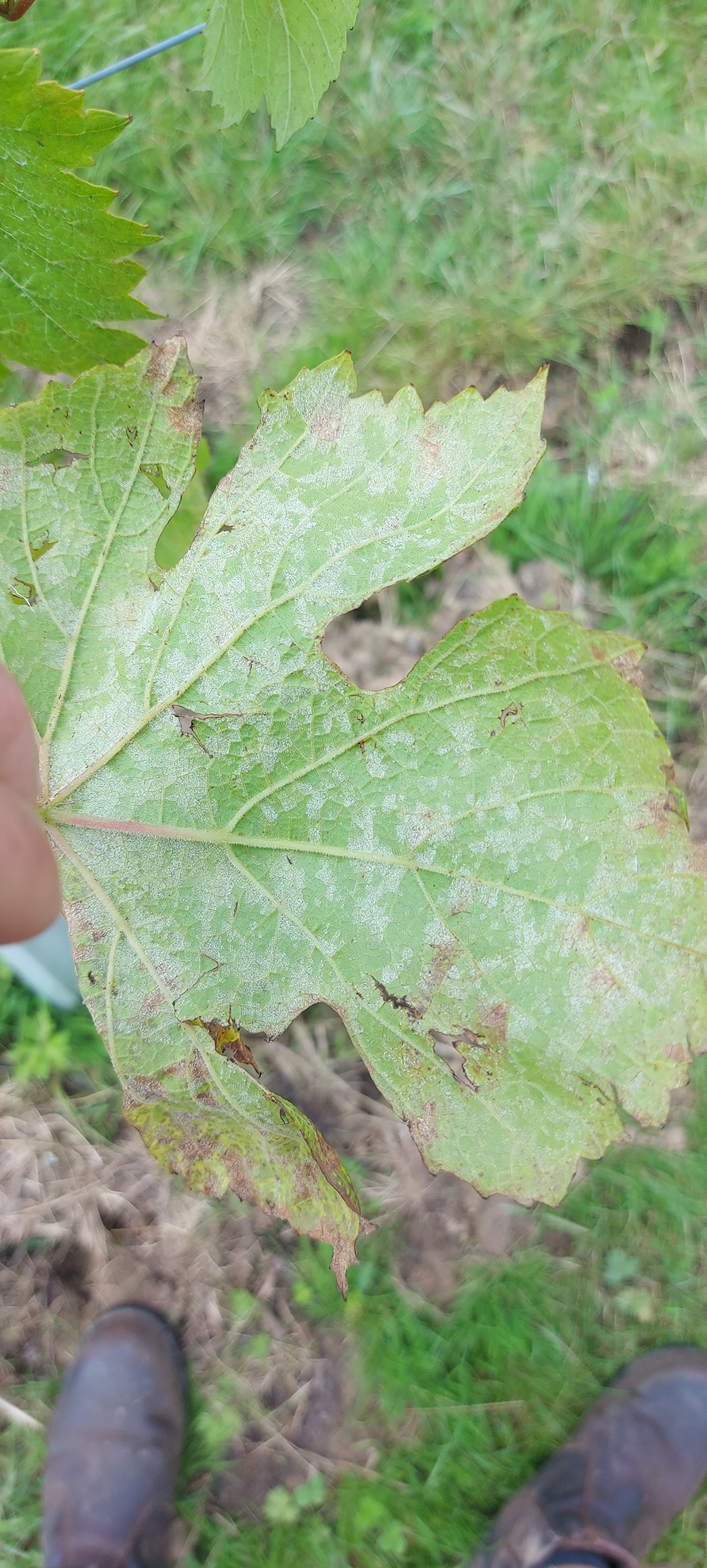

Downy mildew is caused by the fungus-like pathogen called Plasmopara Viticola, which needs a host plant for part of its lifecycle. “It can grow on all green parts of the vine; leaves, shoots and fruit,” explained Joel Jorgensen, consultant viticulturist with Veraison, speaking at a recent WineGB webinar. “If unchecked, and with the right conditions, the infection can spread rapidly causing leaves to brown as they turn necrotic, leaving them unable to photosynthesise. Infection causes the die-back of shoots, early leaf fall, crop losses and the increased chance of attack by other pathogens,” Joel added.

The perfect conditions

“The primary infection is from soil to vine and the rule of thumb 10:10:24 refers to the conditions required for the overwintering spores to germinate,” explained Joel. “These conditions are – 10mm rainfall, while the temperature is 10°C or more over a 24-hour period.” Once the overwintering spores have germinated sporulation occurs regularly under these conditions, which are carried by rain splashes onto wet leaves in the vine canopy. The spores begin to grow hyphae into the leaves. “This primary infection shows up as a yellow oily spot on the topside of the leaf,” added Joel.

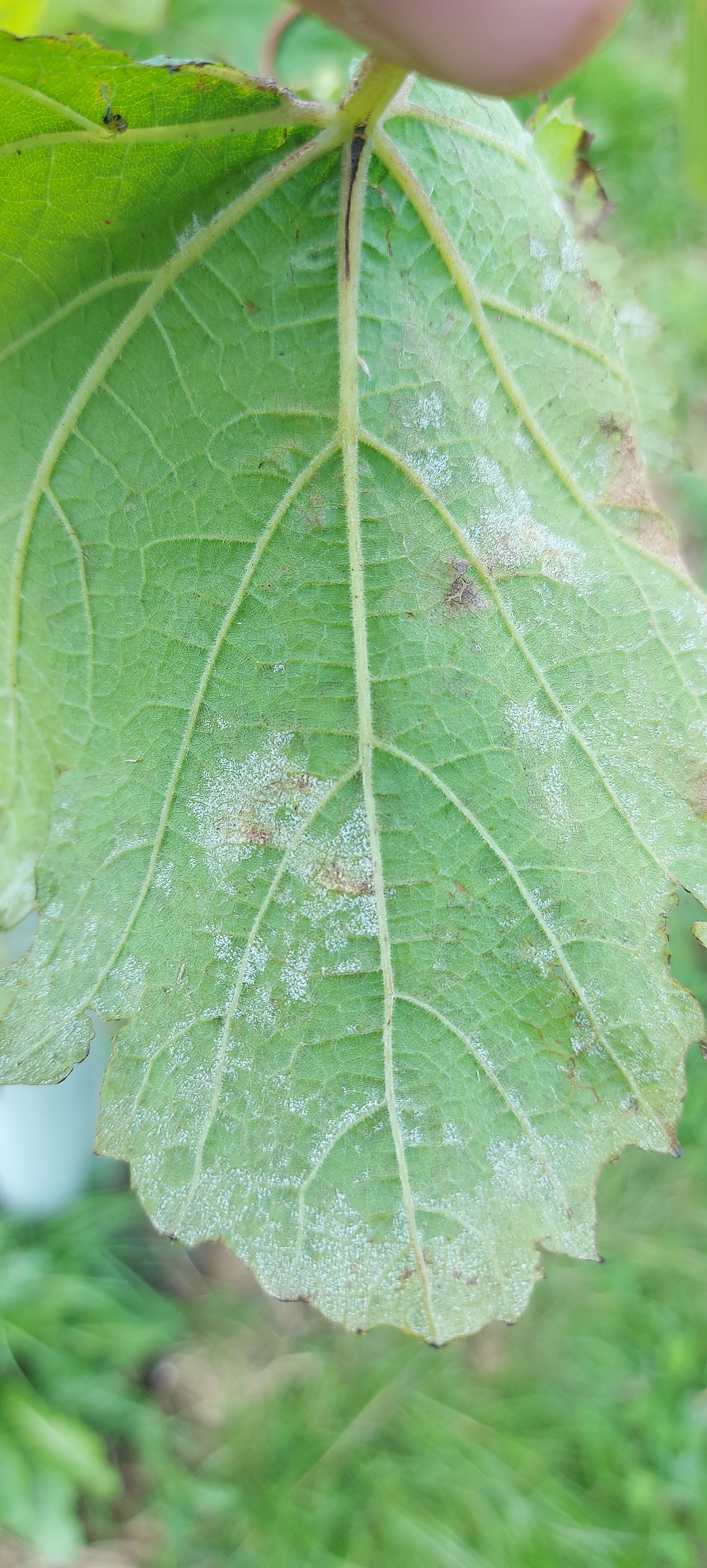

“Within about 24hrs, the oil spot starts to show a spore producing white down on the corresponding underside of the leaf, which is the start of the secondary infection,” explained Joel. These secondary spores are spread on wet leaves and by rain splash to infect other leaves, shoots or berries, and infection can spread fast in the right conditions.

“We have already seen downy mildew on berries this year, as a white down – this is active sporulation and the mycelium can be seen using a spy glass,” commented John.

Overwintering spores are formed in the late summer and autumn from infected leaves or fruit that fall to the ground into the litter or soil. The spores have a thick protective coat, so are able to withstand adverse weather, and are fairly indestructible –they are essentially poised and ready to cause a primary infection next season.

“It is important to know your vineyard, especially its history with disease incidences. If there has been downy mildew in the past then there will be spores in the soil and litter,” added John.

“The secondary infection causes the shoots to start browning, the tips are stunted, and the internal tissue desiccates. This is a particular problem for guyot pruned vines as the damage from the infection can result in no suitable canes to select for the following year. “Unprotected fruit is then easily infected – symptoms include bright white down-like spores on berries and rachis. The berries turn necrotic and remain totally un-harvestable. I know of a grower that lost over £80,000 of fruit by not spraying at the right time,” exclaimed Joel.

Monitoring

Management of downy mildew is dependent on forecasting, by using weather stations that monitor and predict conditions that are favourable for the disease, along with a range of apps that can give disease risk alerts.

“Along with weather monitoring its crucial to get into the vineyard and scout for symptoms,” Joel advises. “This should be done at least every two weeks, ideally weekly or even twice a week, and not just for downy mildew. Walk through the vineyard, mix up your route and really get into the canopy. Get to know your vineyard as there will likely be ‘hot spots’, often the sheltered areas where it is wetter and more humid. And, if you spot symptoms – act immediately,” added Joel.

“We have found more incidences of downy in the sheltered wetter ends of the vineyard, and areas where we have not kept on top of the canopy management,” commented Will.

Many vineyard managers use hand lenses to check suspect spots on leaves, and sample leaves can be taken to do the ‘bag test’ – where suspect leaves are moistened and incubated in a warm place in a sealed bag. If an infection is present it will become evident in just a day or two providing an advance warning of what may happen in the vineyard.

Cultural options

John Bucan’s mantra for downy mildew control is, ‘canopy management, canopy management and canopy management.” He explains that it’s important to get good air flow into the canopy, especially in the fruit zone.

“Maintain a balanced, thinned and trimmed canopy and keep canopy away from the soil. Leaf strip early to get good airflow and allow sprays to penetrate. Keep weeds controlled. Try and maintain airflow in sheltered areas or tree lines around the vineyard. To avoid spreading infection, it’s best not to work in the rain and to regularly clean equipment,” advised Joel.

“Prevention is better than cure,” commented Ben Brown, agronomist from Agrii, speaking at a recent WineGB webinar. “Healthy vines are less susceptible, so ensure a comprehensive nutrition programme,” added Joel.

The armoury

This year the favourable weather conditions for downy mildew have, for some vineyards, corresponded with a lack of suitable plant protection products. “Mancozeb, lost its approval in Europe, but received a three-year extension of approval by CRD (Chemicals Registration Directorate) in the UK after Brexit – but unfortunately the supply chain didn’t anticipate this, so we now have a lack of approved supply,” explained Rob Saunders, Agronomist, Hutchinsons.

“Percos was in short supply for a while so some vineyards may have missed out on using this at a critical time, leaving them vulnerable to downy mildew,” said John. “ Percos is an eradicant as well as protectant and would be the first choice on sites where SL567a (metalalxyl) resistant strains of downy are suspected, especially if intervals were stretched due to continuous wet weather,” added Rob.

“We have limited products, so we have to use them effectively,” explained Rob. “We have Option (cymoxanil) which is somewhat of an eradicate and a short duration protectant, but it’s not very useful by itself in a 10 day spray programme. We can use Frutogard (potassium phosphonate) – but be aware of the 24-day no vine handling exclusion period for any manual work in the vines. I think that copper, which is already restricted, will probably loose approval in time, as it has for use in apple orchards. However, there are agrochemicals that are active on downy mildew that have approval in other crops, but so far haven’t managed to gain approval for vines – unfortunately vines are still considered a crop of minor importance, so manufacturer support isn’t great and CRD require lots of data,” commented Rob.

“Biological control agents such as Romeo, which is fully approved for organic use, can add efficacy to other products,” explained John. “It contains Cerevisane, an extract of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and helps the plant strengthen cell walls and its natural defences. It can be applied up to ten times a year, but it’s not really a stand-alone product and best used with other products.

“Romeo and Fytosave act as elicitors so do not have any curative effect, however they can help the plant with its own defence response,” added Rob.

“In organic production copper is the main defence against downy mildew, but we are restricted to 4kg per hectare per year. I think that Potassium bicarbonate has some effectiveness,” explained Will. “This year we have had to do three copper sprays. However, we regularly analyse our soils for copper, and they remain low, and being organic we have good soil health.

“I also find that our organic vines have much tougher leaves, they are more leathery, and I’m sure this helps the plant not to succumb to disease and make them more resilient, as our vines are usually relatively clean.

“I haven’t found a biological control agent yet that I have confidence in. Some of these sprays are very expensive – and I’m not sure that they work.

“We have full grass cover, which does increase humidity – but the grass does encourage a particular ladybird which I think might eat the spores,” commented Will.

Resistance

“SL567a now has widespread resistance and should not be used on its own. Resistance has started to build over the past seven years or so, and many vineyards have found it has stopped working, as they now have a resistant population,” advised Rob.

John agreed: “ SL567a has been overused on some sites and there are now resistant strains. The product may or may not work – certainly in parts of Sussex. It is not a stand-alone product and needs to be used in combination, the classic has been copper, but it can also be used with potassium phosphonate to help boost efficacy.”

“Some varieties are more susceptible than others. The more fungal-resistant PIWIs are less susceptible but still need to be treated as they are not 100% bomb proof. They do however seem more tolerant of downy mildew and when they have it, it doesn’t seem to spread as fast,” commented Joel.

“It is a mistake not to treat newly planted vines or young vines, as there is a risk of allowing infection to build in the wood,” warns John.

Latest technology

Reports, from a French laboratory, indicate that DNA testing to find out which strains of downy mildew are present in the vineyard are possible. This means that the most appropriate plant protection products can be selected. Cornell University, USA, has trailed robots equipped with UV light to control downy and powdery mildew as the UV light reportedly damages the pathogen’s DNA. There are also reports that robots with sensors are being trialled in vineyards that recognise the early signs of disease, which will allow for spray applications only where needed.

Photos: Joel Jorgensen

Within Secondary infection – white down-like spores on the corresponding underside of the leaf

Infected berries

Necrotic leaf

Infected shoots